Menominee poet Chrystos is a warrior, writer, and arrow in the throat of colonization. Publishing five volumes of poetry, Chrystos is an important voice in the world of literature showing that Native Peoples and Peoples of colour can write, they write well, and they can’t stop from being read and heard.

Menominee poet Chrystos is a warrior, writer, and arrow in the throat of colonization. Publishing five volumes of poetry, Chrystos is an important voice in the world of literature showing that Native Peoples and Peoples of colour can write, they write well, and they can’t stop from being read and heard.

Chyrstos’ poetry is described by Gloria Anzaldua as, “Her words slide into our throats, feed the hungry soul, fill the lost and homeless heart. Her voice binds into wholeness our severed selves with self-esteem. It calls away from the death of invisibility, insists that we be seen and accounted to, no longer banished, no longer vanishing. She leaves her howl inside us.”

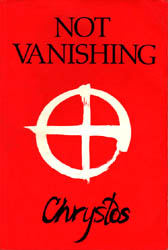

Chrystos’ first collection of poetry, NOT VANISHING, published in 1988, became the highest selling book of poetry in Amerika at the time. No longer in publication, you can read a review of NOT VANISHING.

Read a recent interview between Black Coffee Poet and Chrystos (September 12, 2010) below.

BCP: Why poetry? How did you start writing? What is your process?

CHRYSTOS: My father taught me to read (otherwise, I might still be illiterate) and he had a rich, diverse library which I had complete access to – books floor to ceiling in the hallways. He was self- educated; with only a night school high school degree (I am also self-educated). I was not very well liked by other children (& I thought they were too violent and dumb), so I grew up with my father’s books, many of which were poetry.

I read Plato (though I don’t think I understood him as a child) and Shakespeare. Poetry seemed to be easier than a play or a novel or philosophy. I thought, “Hey I can do this!” I was nine, an age when the stars are closer. My first poems all concerned the virgin Mary (I was razed catholic- not a spelling error), in rhyming couplets. I thought I wanted to grow up to be a nun. I wrote in secret, in bed, by the street lamp. I created a world in my journals (alas, all destroyed by my mother when I was 18) where I could exist, no matter what insanity was flailing about in the exterior world.

Poetry, writing a journal and drawing are still my closest friends. I am not so graceful with actual humans, who betray, can’t comprehend, and are attached to colonizer thought and so on. I would admit that I’m addicted to blank paper, (particularly Belgium rag, which is hard to find).

A long time ago, I had to try to write (high school). But since my 20’s, when I saw the need to address social justice issues in words, my work just “pops out “. A newspaper story, an incident from my life, a book, a song, a garden snake, a sad face I see- I have no idea, actually, how these become poems. A line begins in my mind and won’t leave me alone. I’ve learned to sit and write it down and the rest just flows. I’ve never edited very much-a few words here and there. Generally, I read a new piece to several audiences before I publish it, and I’m grateful to them for their assistance in the editing process.

My forte` is in the oral realm, although I usually play with puns, clichés, double meanings and so on when I type a piece up (I write in longhand). I don’t use a computer because, by now, the link between my writing hand and my mind is seamless. I usually write 2 or 3 poems a week. Some I mail out to friends.

I have not been a part of the publishing industry for some time, because, as my friend, Anne Cameron jokes, “All publishers are pimps”. As a former whore, I’ll comment that no john ever gave me as much trouble as most printing presses. “Editing” is frequently censorship. Ghastly contracts are common. There is, in my experience, very little support for writers. This reminds me of being a single mother supporting three children with no family help.

In order to write, the most important task is to quiet your little mind, to allow the universal to enter and be welcome.

BCP: How long were you putting together the collection that became Not Vanishing?

CHRYSTOS: I was ignored by feminist presses in the usa for many years, about 10, I think. I dragged around to thousands of free readings. Not Vanishing was published by a Canadian press, which embraced (naturally) my hostility to the usa government. I actually put the collection together, all over my living room/dining room floors in about 2 weekends (I worked during the week). The writing of those poems spanned 12-15 years. As an aside for unpublished writers, I was only published to quell the complaints of Canadian women of color (the press until that time had an “all white” list), which I didn’t find out about until much later (&felt badly). The same problem happened with Fugitive Colors which was supposed to be for unpublished writers, but the call flyer didn’t say so.

BCP: Sadly, many of your poems still hold true today. There Is A Man Without Fingerprints, In The Brothel Called America, and Dear Mr. President are some of your poems that I read over and over. Violence against women is still a huge problem (has been since invasion); drugs are still the commodity that brings much suffering but does not suffer in an economic depression; and every world leader has to be sent Dear Mr. President. It’s been twenty-two years since Not Vanishing was published, what do you think of all this?

CHRYSTOS: I had to laugh, because I didn’t realize Not Vanishing was 22 years old (& out of print, sadly). Seems like yesterday. I suppose if I had known that I couldn’t change a thing in the material world of trouble, I would not have bothered to publish. My hope then (& still is) to touch hearts and make change. I feel I have become an icon, whose words are used and not cited, as has happened to many writers of my time. As I said, I’m very uninterested in the publishing world, though I write more now than ever.

Speaking from a stage above a silent audience, is a very colonizer concept, which makes me increasingly uncomfortable. The part of this that does intrigue me is that most of my enthusiastic fans are much younger than myself. My comrades in arms have all died, which is an excruciatingly lonely tiny bit of sand on which to stand.

I don’t know what to think. I’m deeply sad that students are not taught history or herstory or critical thinking or logic. I was very blessed to have an intellectual father who asked me what I thought about what I learned in school.

BCP: How can we make the number of men who are allies to women grow?

CHRYSTOS: We cannot make any group of people do anything. Alas, alas. Otherwise, there would be no despicable posters of President Obama in a Hitler mustache, which is an insult to so many people and such an appalling rewrite of history that I can barely keep my head from spinning around and spitting green vomit. (I didn’t see this movie, The Exorcist, but everyone else has told me about it). He would have been one of Hitler’s first victims in the ovens which Mercedes Benz built.

Men are tortured by colonizers in different ways than women and that is why our society is so violent. I would love to see men mentoring young boys as happened in tribal society. I’m not sure we can re-humanize men of color (who have been used as “sitting ducks”), just as I don’t know if we can turn climate change around.

I suppose I continue to work toward a less abusive society anyway, even though my assessment is that almost everyone prefers some sort of dominance game. We women are the ones who raise our sons, a thought which haunts me. While peer pressure contributes to male violence, what can be our role to change these addictions? I need to clarify that I don’t think euro-immigrant men can be re-humanized, as they don’t know how to avoid playing the master.

BCP: What advice do you have for men who are walking the path of being allies to women?

CHRYSTOS: Where are they?! (an Indian joke) I suppose reading women writers who are revolutionaries is a good beginning. Give a poor poet your car so she doesn’t have to walk with bags of groceries or laundry (another joke). Men are generally deficient in the art of listening (as they’ve been brainwashed into the John Wayne action role), of stepping back, of not having to be in charge, of caretaking themselves. The men I admire most work in an organization called “Men Against Rape”.

If rape ended, we would be in a different world.

BCP: Earlier this year I attended a Women’s Studies class at a local university that focused on Gender and Violence. There was a huge divide between the white women and the women of colour that yelled your poem Maybe We Shouldn’t Meet If There Are No Third World Women Here. The white women took up too much space, would not acknowledge their privilege, and would not listen to the women of colour pointing all this out. I’ve been told this is a common occurrence in Women’s Studies classes and activist circles in North America.

It seems that in terms of white feminists interacting with feminist/womanist/progressive women of colour nothing has changed since before Sojourner Truth spoke in 1851, and since Not Vanishing was published in 1988. That’s over160 years of the same problem. Can things change? If so, how?

CHRYSTOS: White supremacy has beams of support in every aspect of the media, academia, the government, laws, and social interaction. When a person perceives themselves as a victim (as I once did), they are very unlikely to see how they victimize others. My perception comes from my friend, Carmen Lane, that is, most euro-immigrant women are in a fight with white daddy to have more privilege.

My interest has always been a concern for a worldwide end to all oppression, violence, hunger and land theft. Therefore, my political work has ranged over a very diverse area: Palestinian rights, abortion (a non-issue for most lesbians), wife battering, and prisoner issues and so on, which are of no “immediate benefit” to me.

I have no power to change white supremacy, more accurately, colonizer violence. Only those who benefit from it have the power to change it.

I don’t do any anti-racist work anymore–seems a waste of time.

The majority of my efforts now are for Indigenous people (which I consider Palestinians) and prisoners. I think we’ve had the “same problem” for much longer than 160 years— going in back in history one finds continual violence in British suppression of Scots and Irish, Roman invasions, Alexander the Great, the current French attempt to expel Roma people, etc.

I believe there is a poison, similar to ergot in wheat (which probably caused the Spanish Inquisition, Salem witch trials, etc) which causes people to hate, to desire dominance, to insist they alone are right. Maybe it is an inherited mental or social disease. This is an Indian Joke (i.e., true & not really funny, but couched as humor so as to save my life). Everything is always changing—if we could learn to be horses running together in a herd we’d be better off. Still, the problem of that dominant stallion; I don’t suppose neutering would be a popular solution.

BCP: Can you please explain your amazing and very necessary connection of Mestiza (Indigenous and Spanish) women to Native American women?

CHRYSTOS: Much of what I say & write comes from my learning from others. I’m not sure who exactly first touched me with this issue, but I think this was my friend Josie, child of migrant workers, who was deported when I was 8. We were very close, as neglected children often are, and I’ve never recovered from the loss of her, or known how to find her. I had already had previous run-ins (at 7) with the “law” & “injustice”.

Gloria Anzaldua` & I had many intense conversations about this issue (her family were also “migrant” workers) and I would say my understanding (which is limited, I feel, by my inability to speak Spanish) is due to her wisdom.

BCP: Women like you, Gloria Anzaldua, and Audre Lorde broke amazing ground. What new writers do you see doing the same today?

CHRYSTOS: Sadly, I am so out of touch with the writing world that I don’t know who is new. For the last five years, most of my reading has been an exhaustive education in foreign writers, particularly those of Africa, Japan, South America & Britain. I don’t mean to sound ageist, but many young people are not educated enough to attract me. By this, I mean they don’t know very much about what has occurred in my lifetime and who their ancestors & elders are. They believe they are “new”. I was fortunate, because of my Father’s library, to understand I was just the next warrior in line.

I apologize for my ignorance of new writers. This is partially because of my very negative experiences with slam poetry, which is more about ego than craft, at least, that which I was a part of—very briefly.

I’m 63 & I’m sure I seemed like an old grandma. I can’t help it if I don’t agree that “fuck” or ‘whore” or “bitch” repeated 15 times is a piece is poetry. I’ll make a lot of enemies with that statement. My attitude stems from years of hard work to decolonize my mind and educate myself, with no reward in terms of degree or employment. I fight bitterness and consistently lose.

BCP: Do you have a new collection coming out?

CHRYSTOS: I have no publisher. The work I am doing now is so transgressive (of conventional ideas of poetry, “seemliness”, subject matter) that I’m very unlikely to find one, especially in this political climate of neo- white- supremacy. My lover has gotten computer gear together to self publish, but so far, I’m not ready. I have been so frequently misinterpreted by white critics, so often not behaved like a nice compliant author, that I haven’t decided what I want to do.

BCP: What advice do you have for new writers who write about important and pressing issues and topics like the ones you write about?

CHRYSTOS: We live in an extremely abusive & repressive society, which constantly assaults us with garbage in the media. To be a great writer you have to turn off the television, the rap music (which, by the way, was a format taken from women’s Caribbean dub), the telephone & all your relatives’ voices in your head. The place to begin is silence, so you can hear your soul speak in (her) unique voice.

Write about what moves you out of the zombie space colonization would prefer you remain in. Use all 7 senses (the usual 5 plus: humor & psychic). Find an editor who loves your work, rather than is jealous of it. Study craft (grammar books, Babette Deutsch, thesauruses, other writers you admire).

Read your work publicly, as an audience will teach you what is boring, scary, unnecessary & so on. Find an isolated bathroom (parks can be good), with tile walls above shoulder height in which to practice. Old gun bunkers also work –whatever will echo your voice to you. Use an old fashioned tape recorder to listen to yourself. Get a friend to video you.

Educate yourself about your people’s history, language, ancestors & how your particular version of colonization occurred.

Don’t sign any contract without advice from someone who knows the biz. Demand cover control.

Never give up honing your knife. Maintain good ethics & boundaries. And, pray for a clear voice to help others.

BCP: Thank you!

CHRYSTOS: Meegwetch.

Share and Tweet this page; Comment below; and SUBSCRIBE to blackcoffeepoet.com and the Black Coffee Poet YOUTUBE Channel. To DONATE visit my CONTACT Page. Follow me on Twitter @BlackCoffeePoet, and friend Black Coffee Poet on Face Book.

Tune in to BlackCoffeePoet.com this Friday for a video of BCP reading poetry at the rally to STOP the violence against Native women in the stolen land called Canada, February 14, 2009.

To see Black Coffee Poet read live come to the Hart House Arbor Room, Friday September 17, 2010 at 7 Hart House Circle on University of Toronto campus:

I first met Eli Clare in March 2008. He was in town for a talk at the Ontario Institute for Secondary Education and agreed to be interviewed.

I first met Eli Clare in March 2008. He was in town for a talk at the Ontario Institute for Secondary Education and agreed to be interviewed.