Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is a writer and scholar of Michi Saagiik Nishnaabeg ancestry and is a member of Alderville First Nation. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Manitoba, is an Adjunct Professor in Indigenous Studies at Trent University and an instructor at the Centre for World Indigenous Knowledge, Athabasca University.

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson is a writer and scholar of Michi Saagiik Nishnaabeg ancestry and is a member of Alderville First Nation. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Manitoba, is an Adjunct Professor in Indigenous Studies at Trent University and an instructor at the Centre for World Indigenous Knowledge, Athabasca University.

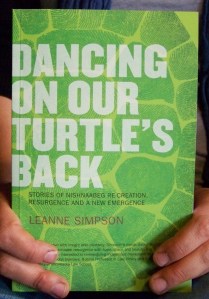

Simpson’s third and latest book is Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence.

ZA: What made you decide to write this book? Who did you write it for?

LS: I wrote this book for an Indigenous audience – for Nishnaabeg people specifically, but for Indigenous Peoples in general. I imagined having the conversation with Nishnaabeg people. I wanted very much to write something for an Indigenous audience instead of a white one – because as Indigenous writers we are so often asked to write something for Canadians. I wrote this book because I was and I am very much interesting in the philosophies and intellect of Indigenous Peoples.

ZA: What challenges arise for you working as an academic in a colonial institution while reclaiming, sharing and living Nishnaabeg culture?

LS: The biggest challenge for me working in a colonial institution is that our knowledge and our people are not there – our intellectuals, fluent language speakers and our Elders are doing the hard work in our communities. The vast majority of students I teach are non-Indigenous and I still see most of the university as a very colonizing force in my community. I know there are decolonizing pockets in particular programs at particular universities and there are some very good people doing very good things, but after twenty years, I don’t for the most part see the university engaged in decolonizing education projects. Because of that, I really limit the amount of time and energy I put into those kinds of institutions.

ZA: How does writing our stories and/or writing ABOUT stories change them?

LS: Well, I am both a writer and an oral storyteller. I think orality is a very important process that is very marginalized and erased because there is so much focus on the written in western thought. Our stories are living and breathing and some of that life gets sucked out of them when they get stuck on the page.

ZA: In the book you state: “I am not so concerned with how we dismantle the master’s house… but I am very concerned with how we (re)build our own house. I have spent enough time taking down the master’s house and now I want most of my energy to go into visioning and building our new home.” What brought you to this conclusion?

LS: I do think analyzing the logistics of colonialism and heteropatriarchy are important, there is no question, but I also think it is very important for us to base our resurgence work within Indigenous thought…and this doesn’t seem to be going on to any great extent in colonial institutions. I’ve always been very interesting in how my Elders think and how my Ancestors thought – and to find that you have to spend a lot of time on the land with Elders.

ZA: You write compellingly about the need for people to “pick up the pieces of our lifeways, collectivize them and build a cultural renaissance and resurgence”. You argue that this has the power to transform settler society as well. Can you explain?

LS: I think it is important for Indigenous Peoples to come from a place of authentic power. I think that in and of itself disrupts the colonial narrative and colonial expectations.

ZA: “Sustainability” is a buzzword we hear a lot these days. What is Nishnaabeg thinking on this concept?

LS: Well, Robin Greene, who has now passed away, but was from Shoal Lake explained to me that sustainability is about figuring out how much you can give up in order to promote the continuous rebirth of life. It is not about resources or exploitation. It is about living as gently as possible.

ZA: Can you briefly outline some of the differences between Nishnaabeg approaches to parenting and those of the dominant society? How do parenting styles relate to domestic violence?

LS: I understand Nishnaabeg parenting to be a very gentle, loving endeavor that was aimed at creating healthy, balanced, grounded individuals with a high degree of respect for diversity and the individual self-determination of others. Childhood should not be something we have to recover from. The Nishnaabeg recognize that children are gifts, that they are constantly learning by doing and from examples. They recognized the fragility of children and the different stages of development. Gentle parenting creates gentle adults.

ZA: You write so eloquently about the beauty and power of Nishnaabeg spiritual beliefs; the role of ceremony, stories and Spirit in resurgence. We all know the history of Christianity’s role in colonization. How does our relationship to Christianity have to change in order for us to pick up our lifeways?

LS: We can’t have a relationship with Christianity that is based on domination, assimilation, conversion, paternalism, charity, oppression, hate or exploitation.

ZA: There are many Nishnaabeg people who may not know their families because they were adopted out, or were cast out by the Indian Act generations ago, or whose families and communities are so dysfunctional that establishing healthy relationships is excruciatingly difficult – even dangerous. There are Nishnaabeg who, for so many reasons, live far from their lands and communities. What advice do you have for those who want to pick up their lifeways and work towards “resurgence”?

LS: Do whatever you can do with what you have. Start. Create communities of healthy like-minded people interested in resurgence. You can find pockets of this kind of work in communities, urban and rural all across Turtle Island.

ZA: In the last chapter you write: “Our social movements, organizing and mobilizations are stuck in the cognitive box of imperialism …” What do you mean by this and what do you advocate instead?

LS: Living our political traditions is important, so I wanted to start the discussion, or perhaps continue the discussion some other Indigenous academics have started, about what our own philosophies of organizing and mobilizing look like. I think we need to stop looking for recognition, stop responding to the agenda of the colonizer and place resurgence at the centre of our lives and our work.

Zainab Amadahy is a writer and activist of African American, Cherokee and European heritage.

Zainab Amadahy is a writer and activist of African American, Cherokee and European heritage.

Her publications include the novel Moons of Palmares (1998, Sister Vision Press) as well as an essay in the anthology Strong Women’s Stories: Native Vision & Community Activism, (Lawrence & Anderson, 2004, Sumach Press).

Most recently Zainab contributed to In Breach of the Colonial Contract (Arlo Kemp, ED) by co-authoring “Indigenous Peoples and Black People in Canada: Settlers or Allies”. Many of her recent articles can be found on rabble.ca.

As an artist and activist based in Toronto Zainab has worked with a variety of organizations to support decolonization, social justice and First Nations struggles.

Tune into Black Coffee Poet June 8, 2012 for a video of Leanne Simpson reading from her book “Dancing On Our Turtle’s Back”.

Pingback: LEANNE SIMPSON READS FROM “DANCING ON OUR TURTLE’S BACK” | Black Coffee Poet

Pingback: WIN A COPY OF “DANCING ON OUR TURTLE’S BACK” + A GRAND PRIZE | Black Coffee Poet

Pingback: The Round-Up: June 12, 2012 | Gender Focus – A Canadian Feminist Blog

Pingback: OP ED: ANTI VIOLENCE AGAINST INDIGENOUS WOMEN AND RESURGENCE | Black Coffee Poet